The Duerrnberg mine – a major competitor

The Duerrnberg near Hallein, Austria’s second important Iron Age site, is situated some 15 kilometres south of Salzburg. The rich salt deposits of the Duerrnberg already attracted people in the Late Stone Age and the Bronze Age. However, unlike in Hallstatt, organised salt mining did not start until the first half of the 6th century BC.Hallstatt and Duerrnberg - similarities and differences

Early salt production in Duerrnberg

The early mining phase

Feeding the miners

Tools used for mining

Finds of tools and clothing

Techniques used at the Duerrnberg mine

Changes in the 4th century

Ongoing development at the Duerrnberg mine

End of mining in Duerrnberg

Hallstatt and Duerrnberg - similarities and differences

After Hallstatt, Duerrnberg near Hallein is the second largest, supraregional salt producing site of the eastern Alpine region. The two places have much in common, but there are also marked differences. Thanks to the easily accessible location in an Alpine border region, Duerrnberg is in a better position than Hallstatt to build up durable economic structures. All the more surprising, then, that Hallstatt rather than the Duerrnberg has been the leader in underground salt mining. Perhaps the economy of the Salzach Valley was focused on the Salzach-Pongau region copper mining until well into the Iron Age, which would have prevented the exploitation of the rock salt deposits.Early salt production in Duerrnberg

The salt deposits in Duerrnberg had most certainly been known since the 5th millennium BC, as evidenced by numerous surface finds. After decades of intensive research, it is today generally accepted that the Duerrnberg salt deposit was only used from the 6th century BC onwards. This economic turn took place at a time when a considerable concentration of settlement occurred in the Salzburg Basin, suggesting that 'groups of entrepreneurs' from both the Alpine foreland and the Salzburg Basin were involved in the exploitation of the salt deposits at the Duerrnberg, striving to meet the increasing demand for salt in the 5th and 6th centuries BC in South Germany, Western Austria and Bohemia.The early mining phase

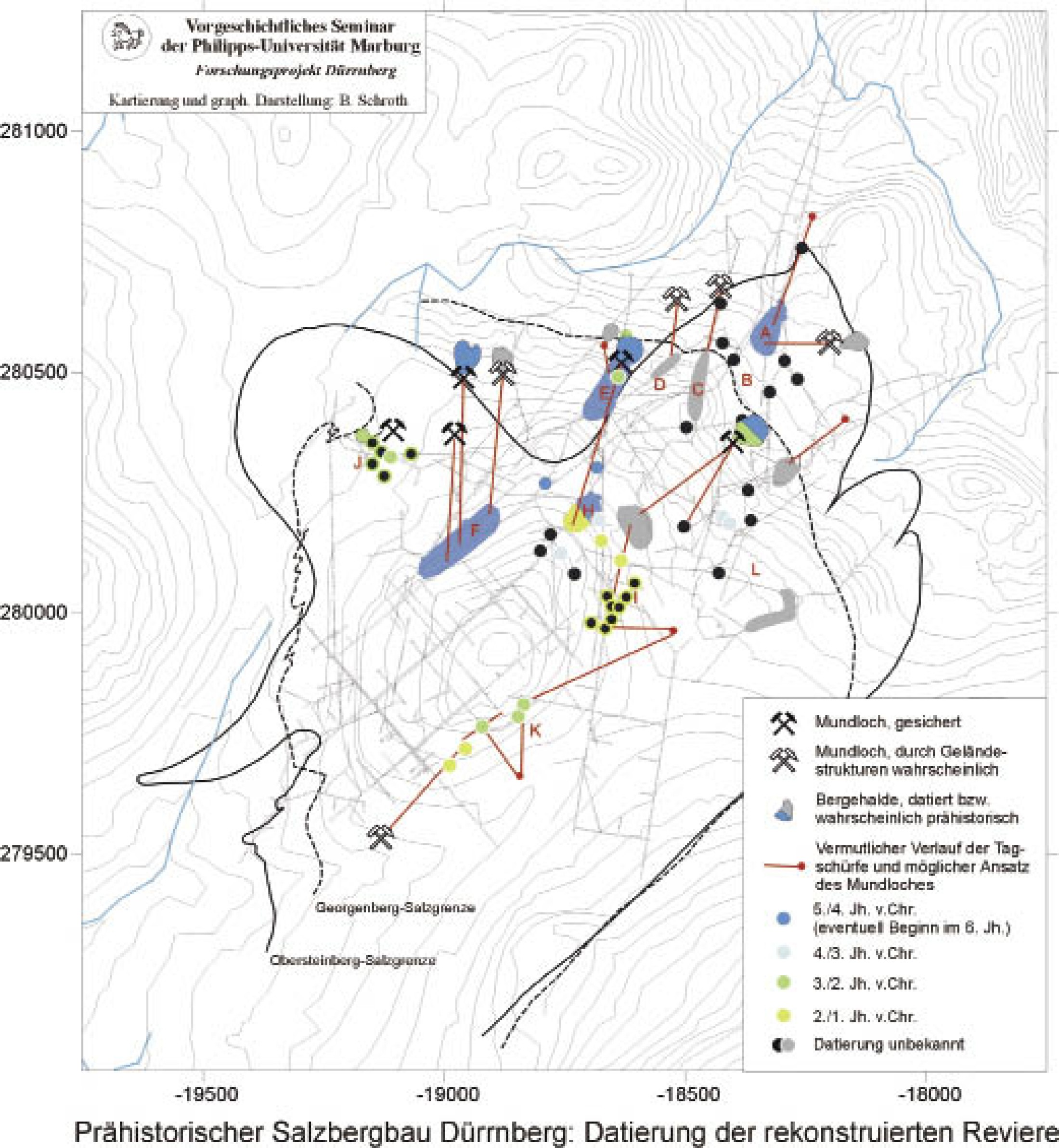

Underground investigations started in 1989 reveal that several mines were operating simultaneously in the 6th century BC, suggesting considerable expert knowledge. From the beginning, several mine mouths were laid out in the soft flanks of the Hahnrain Mountain and at the Lettenbuehel. These were gradually enlarged and two more mines had been opened up by the beginning of the 4th century BC. Conservative estimates put the number of miners maintained by the local Duerrnberg community at around 200.Feeding the miners

Botanical analysis of the human excrement suggests that the miners probably worked the mine throughout the year. The analysis implies seasonal food: traces of fresh wild fruit prove that the miners worked in summer and autumn. Data provided by pollen analysis are more difficult to assess. So far, traces attest to mining activity in winter and spring. Pollen grains from other summer flowering plants cannot be interpreted with any real degree of accuracy, since they might have been ingested with the food. The main dish reconstructed for the Duerrnberg resembles the Hallstatt Ritschert. The Duerrnberg miners ate almost exclusively boneless meat. So far, no remains of animal bones have been found in the bottom settlements, but traces of muscle fibres in the excrement reveal that the miners did actually have meat in their diet.Tools used for mining

Right from the beginning, the Hallein miners relied on a new tool, the iron pick. The composite Haselgebirge rock of the Duerrnberg was worked by a short-handled pick in combination with heavy socketed axes and adzes as carpentry tools. Grindstones were of quartzite and siliceous rock. Several of the tools come from the region south of the Alpine divide, and some of these unspectacular finds may suggest the involvement of the Alpine hinterland.Finds of tools and clothing

Analyses of the animal bone assemblage of the Ramsau Valley suggest that this region was home to the Duerrnberg sheep breed. Tools and garments found in the salt mine show that the miners’ equipment was very functional, but also very uniform and very probably standardized, as revealed by animal hides, wood tools and tapers.Excavations have revealed that the corresponding workshops existed in the Ramsau Valley. The hides come mainly from cow, which was also the raw material for a large part of the protective clothes and the functional items such as straps, hauling sacks, bags, shoes and so on. The large amounts of animal bones suggest that cows not only supplied the mining community, but that the meat was salted on the spot for export.

Techniques used at the Duerrnberg mine

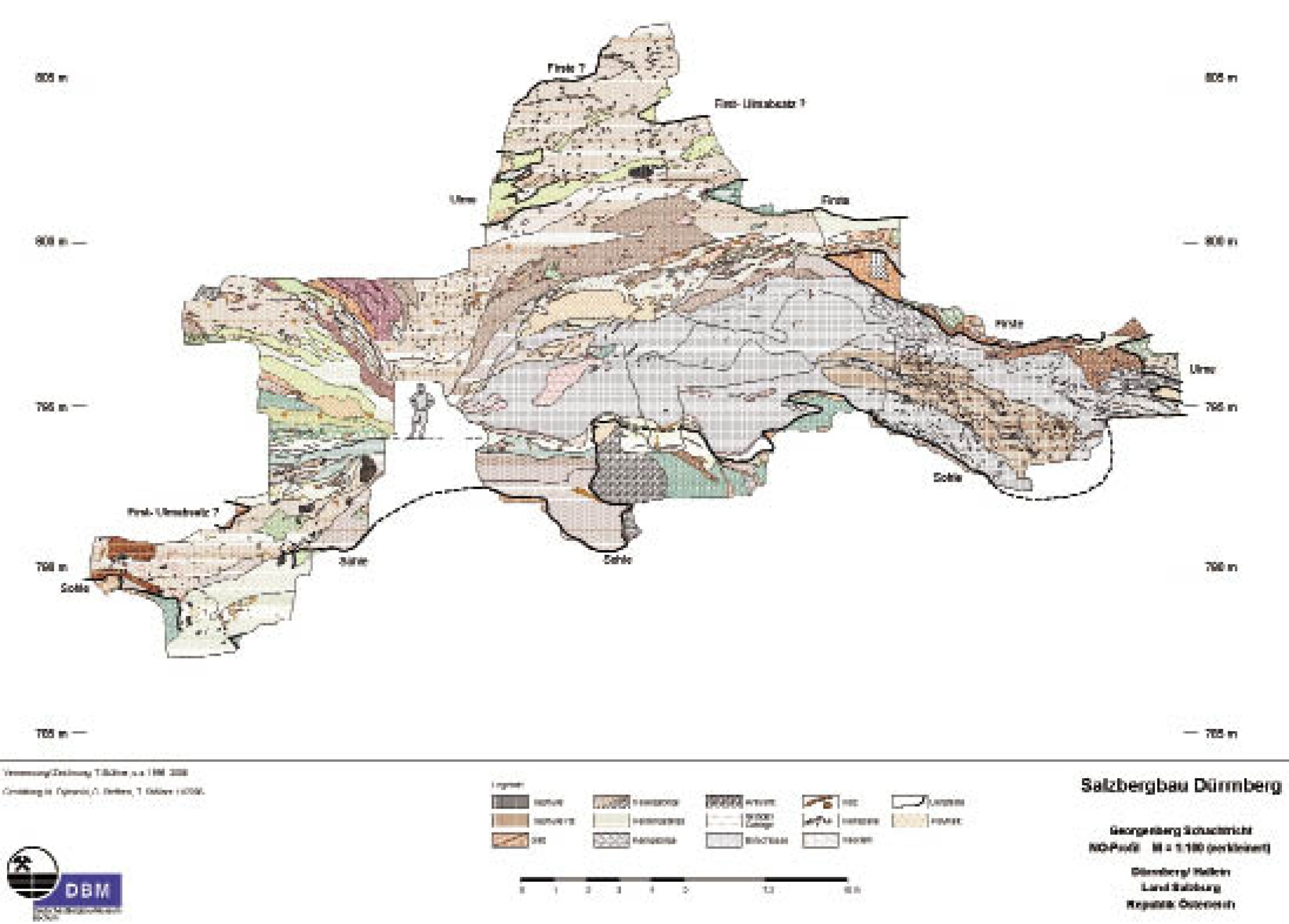

At the Duerrnberg, salt was most certainly not only mined in the form of large pieces, but also in the form of chippedup Haselgebirge, rich in salt and particularly suited for the preservation of meat. There are considerable differences between the individual mining zones: the Ferro-Schachtricht was operated very selectively, aiming at the rich core-salt areas, while in other areas mining was aimed at the Haselgebirge rich in salt. The working method applied in Hallstatt in the Early Iron Age was further developed at the Duerrnberg. This development shows most clearly in a change of the mining technique: from mining of single salt layers with floating intermediate levels, to mining in tiered gallery levels.Other mines employed overhand stoping where the gallery was extended stepwise upward, as witnessed by the unique excavation profile of 34 x 15 metres in the Georgenberg site. The temporary standstill in the 4th century BC, attested by thick clay strata, was due to the penetration of water, and a resumption in mining activities is evidenced for the late 3rd century BC. Generally, salt mining again intensified at that time. There are several other mine workings that show traces of water penetration, and the dead bodies, reported as unearthed in 1577 and 1616, the so-called 'Men in the salt', may well be linked to this flooding.

Changes in the 4th century

The male body recovered from the Georgenberg might be directly related to the current excavation site. It is an open question whether these disasters were associated with the short climatic deterioration of the 4th century BC, and whether they caused the final cessation of the mining in the East Group in Hallstatt. Considering the Alpine foreland seems to have been sparsely settled in the 4th century BC, a crisis in the settlement landscapes north of Hallstatt and the Duerrnberg would seem probable. That the Duerrnberg continued to produce salt at the time testifies to its economic power. Evidence in support of contacts with the inner- Alpine region is even more tangible for that period, and contacts with South-West Germany and the East lasted until the late 4th century and the 3rd century. As an economic centre, the Duerrnberg survived into the late La Tène period.Ongoing development at the Duerrnberg mine

The mining activities were not limited to the reactivation of old deposit areas; in the western and eastern part of the deposit, new fields were developed, although smaller now than previously. So far, up-to-date research is lacking for nearly all these areas, and we can only sketch a tentative picture. Some findspots are better known and have recently been investigated. They have revealed a surprisingly uniform material culture hardly different from that of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods, a fact likewise evidenced by the continuous development of mining at the Duerrnberg.End of mining in Duerrnberg

One interesting issue is the end of the Iron Age mining on the Duerrnberg. On the whole, mining activities date to the end of the Iron Age, but we have very few finds from after the middle of the 1st century BC. Some radiocarbon data might suggest even more recent activities in the early Imperial Era, but they cannot yet be assessed in relation to the salt mining of the early La Tène period. Surface finds known so far confirm the slow decline of salt mining. At the beginning of Roman rule in the East Alpine region, salt was only mined on a local basis.(Stoellner, T. – Moser, S.)